How was Campaign Finance Affected after Citizens United?

The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission created new paths for campaign finance. What has changed? Tony Corrado joins Mike Petro to discuss CED's detailed report (below).

Executive Summary

The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission created new paths for unlimited contributions and spending in federal elections. The court overturned the long-standing ban on corporate expenditures in federal elections, affirming the First Amendment right of corporations—and by extension labor unions—to spend funds from their general treasuries to support federal candidates, so long as these expenditures are made independently without coordinating with the candidates they support. The Citizens United ruling also paved the way for a subsequent appellate court decision, SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, that sanctioned the creation of Super PACs, political action committees that may raise and spend unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, labor unions, and interest groups, so long as they do not make donations to candidates and spend money independent of candidates. These court decisions raised the prospect of a new sphere of unlimited funding in federal elections with consequences for the ways campaigns are financed.

As part of CED’s continuing effort to understand the changes taking place in campaign finance, we conducted an analysis of the financial activity in the 2014 and 2016 elections. We examined the independent expenditures in each of these elections and contributions to the top Super PACs to assess the behavior of corporations, business groups, labor unions, and other organizations in the post-Citizens United regulatory environment. Such an analysis does not encompass all election-related spending, since current laws do not require disclosure of all money raised and spent by nonprofit social welfare groups and other tax-exempt organizations. Even so, our findings provide an overview of the current landscape of campaign finance and the effects of Citizens United.

An Overview of Federal Campaign Financing

Federal elections are now financed by a diverse group of stakeholders, including candidates, parties, PACs, and other organizations. Candidates, parties, and PACs raise money subject to contribution limits and disclosure rules that require public reporting of their contributions and expenditures. Super PACs are not subject to contribution limits but are required to disclose their contributions and expenditures to the public. Other organizations, including non-profit social welfare advocacy groups, trade associations, and labor unions, may accept unlimited contributions or use money from their general treasuries to finance political activity and are only required to disclose the amounts they spend and the candidates they support, not their sources of funding.

Two spheres of financial activity, therefore, define campaign funding: one based on limited contributions from individuals (candidates, parties, and PACs), the other on unlimited contributions (Super PACs and other organizations).

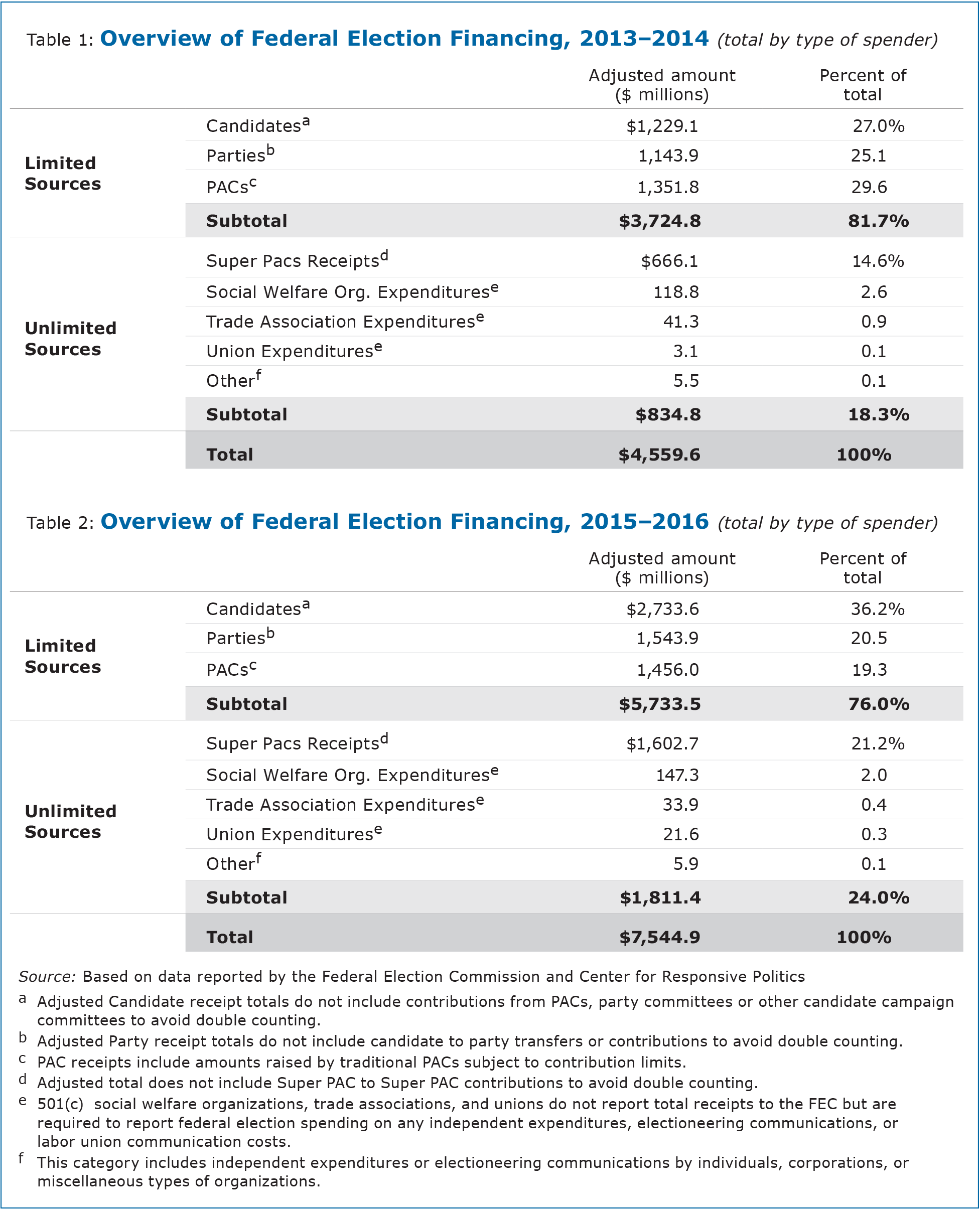

Most of the money raised in federal elections comes from donations made by individuals to candidates, parties, and PACs that are subject to contribution limits and full public disclosure. In the 2014 and 2016 elections, more than 75 percent of the money raised or spent on election activity came from limited individual contributions.

The effects of Citizens United and the advent of Super PACs are reflected in the unlimited sources of funding, which include all monies raised or spent to advocate the election of candidates that come from organizations that can accept unlimited donations from individuals, corporations, labor unions, and other groups. These sources include Super PACs, trade associations, labor unions, and tax-exempt social welfare groups established under section 501(c) of the tax code. (See Table 1.)

Independent Spending

Prior to Citizens United, corporations, trade associations, and labor unions could spend money independently in support of candidates, but they had to use PAC money raised from limited, voluntary individual contributions. Citizens United changed the law by allowing these organizations to use unlimited contributions or money drawn from their general treasuries to finance independent expenditures in support of candidates. This change was expected to produce a surge in business spending. We found little to support this expectation. In fact, few business corporations or associations have made independent expenditures in recent elections.

No major corporation has spent money independently in support of a candidate. Only two companies in 2014 and ten in 2016 made independent expenditures from corporate funds, and these companies spent relatively minuscule amounts.

A small number of business associations and professional organizations have spent money independently, with total spending of $39 million by 7 organizations in 2014 and $34 million by 10 associations in 2016. More than 85 percent of the total in each election was due to the spending of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which has been active in elections since long before Citizens United.

In all, monies spent independently by business companies and associations represented less than five percent of the monies that came from unlimited sources in 2014 and 2016.

Super PAC Contributions

Rather than spend money directly in support of candidates, political stakeholders may also support candidates indirectly by making contributions to Super PACs that favor a stakeholder’s preferred candidate. Super PACs spent $345 million on independent expenditures in 2014 and $1.1 billion in 2016, which greatly exceeded the total independent spending of all other entities freed to spend money in support of candidates by Citizens United.1

To determine the sources of this funding, CED examined the contributions received by the top Super PACs, which were responsible for 87 percent of the total monies raised by Super PACs in 2014 and 94 percent of the total raised in 2016.2 We catalogued these contributions based on the type of donor to determine the different sources of Super PAC financing. Our analysis of the contributions received by Super PACs revealed the following:

- Individual donors are the primary source of Super PAC money and were responsible for 60 percent ($299 million) of their total receipts in 2014 and 68 percent ($1.1 billion) in 2016.

- Business corporations were the source of about 5 percent of Super PAC receipts in 2014 and 6 percent in 2016, although the $95 million contributed in 2016 represented a significant increase over the $25 million contributed in 2014.

- Major corporations have not been active participants in Super PAC financing. Publicly held companies were the source of less than one percent of total Super PAC funding and most of this money came from only a few companies.

- Trade associations have been an even less important source of funding, giving $11 million in 2014 and $12 million in 2016, which represented two percent of total Super PAC funding in 2014 and less than one percent in 2016. These sums were due almost solely to contributions by the National Association of Realtors.

- Labor unions have also provided a small share of Super PAC funding, but have played a larger role than the business community. Labor unions have established their own Super PACs and in the last two elections have contributed $32 million more than all businesses and trade associations combined. 5 Report

- Interest groups, including many that are organized as 501(c)(4) social welfare advocacy groups, were responsible for less than 5 percent of Super PAC receipts, with total donations of $15 million in 2014 and $70 million in 2016. Because these groups are not required to disclose their sources of funding, we were not able to conduct a detailed analysis of the sources of a group’s financing.

The Limits of Transparency

A complete analysis of the landscape of campaign financing is limited by the current state of disclosure rules. Under the regulations adopted by the Federal Election Commission, social welfare organizations established under section 501(c) of the tax code are not required to disclose their sources of funding. While we can assume that independent expenditures by trade associations are drawn from monies raised from business sources and those by labor unions are from labor sources, no simple assumption can be made about the sources of funds used by social welfare organizations, which financed $119 million of independent expenditures in 2014 and $147 million in 2016. The organizations that are not encompassed in our analysis were thus responsible for 2-3 percent of the overall financing in the past two elections.

Most of this money was spent by a small number of groups, with the top six spenders responsible for a major share of the money spent independently by social welfare organizations in the past two elections. These top spenders constituted a mixed group of organizations that likely received funding from diverse sources. But due to the lack of disclosure, meaningful assumptions about the relative role of different sources are not possible.

Conclusion

The campaign finance landscape has changed since Citizens United. New sources of funding and new types of organizations have become involved in federal elections. The major change is the rise of Super PACs, which have become a significant source of campaign spending. Yet, even with these changes, the vast majority of the money in federal elections still comes from limited, disclosed contributions made by individual donors to candidates, parties, and PACs. When the unlimited contributions made by individuals to Super PACs are included, the vast majority of the money raised to finance federal election activity—88 percent in 2014 and 90 percent in 2016—came from voluntary contributions made by individuals.

Corporations, labor unions, and other organizations have become more active participants in campaign finance and are spending substantial amounts, although this activity represents a minor share of the money flowing into federal elections. Our analysis indicates that business corporations and trade associations have not responded to the Citizens United ruling by substantially devoting significant resources to the new opportunities for political spending created by the decision. From what can be discerned from public reports, the responses of the business community and labor community have been relatively equivalent in terms of their role as sources of unlimited money in the election process: neither has pursed extensive independent spending and neither has proven to be a source of funding that is driving the growth of Super PAC fundraising, although both have contributed to the changes taking place in minor ways.

There has been a rising role and outpouring of money from interest groups, particularly organizations that raise money outside the realm of public disclosure. The role of these organizations continues to be a cause for concern, since their transactions in election campaigns are not subject to effective and full public disclosure. Further growth in this component of election finance would impair the public’s ability to know who is behind election spending and thereby decrease the accountability in the campaign finance system.

Introduction

The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission created new paths for unlimited spending and unlimited contributions in federal elections. The Court overturned the long-standing ban on the use of corporate money in federal elections, affirming the First Amendment right of corporations—and by extension labor unions—to spend funds from their general treasuries to advocate the election or defeat of a federal candidate.3 While the Court upheld the ban on corporate contributions to candidates, it allowed corporations to spend money on advertisements or other election activities that urged citizens to vote for or against a candidate, so long as they do so independently without coordinating with the candidates they support. The Court also struck down the prohibition on the use of corporate funds to finance electioneering communications (broadcast advertisements that feature a federal candidate and air in close proximity to an election but do not specifically ask citizens to vote for or against a candidate); this form of advertising was first regulated in 2002 by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. Corporations were thus allowed to spend unlimited amounts of money directly in support of federal candidates.

The Citizens United ruling paved the way for a subsequent decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in SpeechNow. org v. Federal Election Commission, which gave rise to a new form of political committee that came to be known as a Super PAC.4 Super PACs are political action committees that solely spend money independently in support of candidates; they do not make contributions to candidates. The court struck down the contribution limits applied to such independent, expenditure-only committees, holding that independent expenditures pose no risk of corrupting candidates, so there is no government interest in limiting the contributions they receive to finance their expenditures. Super PACs may, therefore, accept unlimited contributions from corporations, unions, interest groups, or individuals, and use these funds to spend unlimited amounts of money in support of candidates.

These court decisions presented the prospect of a new sphere of unlimited funding in federal elections with potentially far-reaching consequences. Businesses, trade associations, nonprofit advocacy groups, and labor unions, as well as individuals, could now support candidates either directly by making unlimited independent expenditures or indirectly by contributing unlimited sums to Super PACs or other organizations engaged in independent spending. At the time, the Citizens United decision was announced, many observers, including President Obama, predicted that the ruling would unleash a flood of corporate and interest group money in elections, thereby increasing the influence of special interests in the political process.5 Since then, the decision has become a lightning rod for public criticism, with some opponents even calling for a constitutional amendment to prohibit the spending permitted by the decision.6

CED shared the concern about the potential consequences of Citizens United when the Court issued its opinion. Among our principal concerns was whether the decision would spur a new wave of unlimited campaign funding and whether this would revive the pressures to engage in political giving experienced by the business community when the national parties could raise unlimited soft money donations. These questions were informed by our long-standing interest in campaign finance. Since 1968, CED has examined the problems associated with campaign finance and advocated solutions to improve how elections are funded. We have expressed continuing concerns about the role of money in the political process and its effect on the health and vitality of our democracy and have issued a series of reports to inform the public and the business community about the problems of the campaign finance system and the need to promote greater participation and accountability in political finance.7

As part of our efforts to understand the changes taking place in campaign finance and the effects of Citizens United, we conducted an analysis of the financial activity in the 2014 and 2016 elections. We sought to determine how the sources of funding in federal elections may have changed in response to the more permissive regulatory environment established by the Court’s decision. As an organization of business leaders, we were particularly interested in the response of for-profit corporations and business organizations to the Citizens United and SpeechNow.org decisions. To what extent have corporations changed their behavior by making independent expenditures or contributing money to Super PACs? What role has the business community played in the surge of spending that has taken place in recent elections? And how does business community activity compare to that of labor unions and interest groups?

To answer these questions, we examined the independent expenditures and electioneering communications made in the 2014 and 2016 elections, as well as the contributions to Super PACs, to assess the response of corporations and business organizations, labor unions, and other organizations to the new regulatory environment. In all, our study included US$429 million of independent expenditures and electioneering communications spending, and $1.8 billion of disclosed, itemized contributions to Super PACs, including more than 5,100 contributions from sources other than individual donors. In other words, we examined the monies that are defined as campaign finance under current law and are reported as such under current regulations.

We recognize that such an analysis does not include election-related spending that does not qualify as campaign spending under current rules. Most importantly, we do not capture monies raised or spent by nonprofit social welfare groups organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code or other organizations on activities that do not expressly advocate the election of a candidate and therefore are not regulated by campaign finance laws. These activities include nonpartisan voter registration drives, issue advertisements, or advertising that features a candidate but is not aired near an election, so it does not qualify as an electioneering communication. Any monies spent on these activities do not have to be disclosed to the public. But it is essential to note that such spending was an issue prior to Citizens United and the decision did not affect these regulations. The major change resulting from Citizens United was that these groups were also permitted to spend money independently to expressly advocate a candidate—to engage in campaign spending. These expenditures are included in our analysis, although, as we note below, disclosure remains a concern since these groups are not required to disclose the source of the funds used to pay these costs under current regulations. Such spending by these so-called “dark money groups” is a problem in the campaign finance system since it reduces the accountability and transparency in the electoral process.

Our findings thus provide an overview of the current landscape of campaign finance. In this way, they provide a clearer understanding of the sources of funding in federal elections and the effects of Citizens United.

An Overview of Federal Campaign Financing

Federal elections are now financed by a diverse group of stakeholders, including candidates, parties, PACs, and other organizations. Candidates, parties, and PACs raise money subject to contribution limits and disclosure rules that require public reporting of their contributions and expenditures. Super PACs are not subject to contribution limits, but are required to disclose their contributions and expenditures to the public. Other organizations that are not Super PACs can spend money independently as a result of Citizens United, including non-profit social welfare advocacy groups, trade associations, and labor unions. These non-profit organizations are also known as 501(c) groups because they have taxexempt status under section 501(c) of the Internal Revenue Code. These organizations may accept unlimited contributions or may use unlimited amounts of money from their general treasuries to finance independent expenditures, but they are only required to disclose the amounts they spend and the candidates they support, not their sources of funding. However, these organizations are established for purposes other than political activity, so Internal Revenue Service rules allow them to spend only a minor share of their total funding on political activity.

Two spheres of financial activity therefore define campaign funding: one based on limited contributions (candidates, parties, and PACs), the other on unlimited contributions (Super PACs and 501(c) organizations). Understanding the relative role of limited and unlimited monies is one way to place recent regulatory changes in broader context and gain insight into the changes taking place in the sources of campaign financing.

Most of the money raised in federal elections comes from limited contributions made by individuals to candidates, PACs, and party committees. In the 2014 and 2016 elections, more than 75 percent of the money raised or spent on election activity came from these entities, which are allowed to receive limited contributions (although candidates are permitted to make personal contributions to their own campaigns without limit8 ) and are specifically prohibited from accepting contributions from corporations or labor unions (see Tables 1 and 2).

The effects of Citizens United and SpeechNow.org are reflected in the unlimited sources of funding in the 2014 and 2016 elections, which include all monies that were raised or spent to advocate the election of candidates. Groups or organizations that are allowed to support candidates with unlimited contributions, including donations from corporations, labor unions, or nonprofit social welfare organizations, were responsible for 18 percent ($835 million) of total campaign funding in 2014 and 24 percent ($1.8 billion) in 2016. Super PACs were responsible for most of this money, raising $666 million in 2014 and $1.6 billion in 2016, which represented 14 percent of total campaign funding in 2014 and 21 percent in 2016. More notably, these committees contributed 80 percent in 2014 and 88 percent in 2016 of the unlimited money raised or spent in these two elections.

While Super PACs are required to disclose their receipts as well as their expenditures, nonprofit organizations are not. Nonprofits are now permitted to raise and spend money independently in support of candidates. These organizations are often formed for a primary purpose other than influencing elections, so disclosure of the sources of their funding is beyond the scope of campaign finance disclosure laws. They do, however, disclose the amounts they spend on independent expenditures advocating candidates or on electioneering communications to the Federal Election Commission (FEC). Accordingly, these expenditures are noted in our summary of campaign financing, rather than the amounts of money they raise.

After Citizens United, three basic types of nonprofit organizations may participate in the financing of federal elections: nonprofit social welfare or policy advocacy groups organized under Section 501(c)(4) of the tax code, trade associations organized under Section 501(c) (6), and labor unions organized under Section 501(c)(5). These organizations were responsible for only a small share of election spending, with a combined total of less than 4 percent of the money reported in both 2014 and 2016, but the amounts they spent are not insignificant. Policy advocacy groups spent $119 million in 2014 and $147 million in 2016. Trade associations spent $41 million in 2014 and $34 million in 2016, while unions reported $3 million in 2014 and more than $21 million in 2016. Much of the money reported by unions consisted of the costs of communicating their support of a candidate to their members, which are known as communication costs, and were permitted under federal law prior to Citizens United. All labor spending therefore is not a result of Citizens United, but most of labor spending is.

The post-Citizens United regulatory environment has clearly led to a change in the sources of campaign money, with a substantial share of funding now coming from entities that are not subject to contribution limits. This is primarily due to the rise of Super PACs, which have become the primary recipients of unlimited contributions. Other organizations allowed to spend money advocating candidates have also been active, but their spending constitutes a relatively small share of the money in federal elections.

Independent Spending

Prior to the Citizens United decision, corporations, trade associations, and labor unions could spend money independently in support of candidates, but they could do so only if they used PAC money raised from limited, voluntary individual contributions. Citizens United changed the law by affirming the right of corporations to spend money independently using money from their corporate accounts. CED examined the independent expenditures and electioneering communications in the 2014 and 2016 elections to determine how this ruling has affected corporate behavior. We found little to support the expectation that Citizens United would result in significant spending by business corporations. In fact, few business corporations or associations have made independent expenditures in recent elections.

In the past two elections, no major corporation has spent money independently to advocate the election of a candidate. Only two companies in 2014 and ten in 2016 made independent expenditures, and these companies spent relatively minuscule amounts—a total of less than $70,000 in 2014 and less than $700,000 in 2016 (see Table 3). In 2014, the only companies to spend more than $100 were Page Communications, LLC, which spent $52,229 on billboard advertising in support of candidates in North Carolina, and Wallace and Wallace, Inc., which spent $14,900 on billboard advertising in a House race in Georgia. In 2016, two companies were responsible for most of the spending: Trulia, Inc., which spent $345,000, and Hampton Creek, Inc., which spent $173,297. In this regard, the two most recent elections were not unique. In 2012, no Fortune 500 company spent money independently and only four companies used corporate resources to support a candidate, financing a combined $255,000 of independent expenditures.9 One company, Melaleuca, Inc., was responsible for most of this sum, spending more than $200,000 in support of Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney. By way of comparison, labor unions spent more money independently from their treasuries than corporations have. In 2014, five labor unions made $445,000 of independent expenditures, while in 2016, fourteen labor organizations spent $12.1 million.

Business corporations may decide to rely on a trade association or other business organization to conduct campaign activities in support of candidates who share their views, rather than spend money on their own. Yet, even when the expenditures reported by trade associations or other business organizations are considered, the role of business spending is relatively insignificant. Few trade associations or business organizations spent money independently, with total spending of $39 million in 2014 and $34 million in 2016. More than 85 percent of this total in each election was due to the spending of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which reported $35 million of independent expenditures in 2014 and $29 million in 2016. The only other trade organizations to spend substantial amounts were the American Chemistry Council, which spent $2.3 million in 2014 and $1.8 million in 2016, and the National Association of Homebuilders, which spent $1.3 million in 2016.

While the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has spent substantial sums in each of the past two elections, it should be noted that they have been active in elections since long before Citizens United. A recent study estimates that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce spent at least $20 million in 2006 and $36 million in 2008 on issue advertising and other election-related activities that did not expressly advocate the election or defeat of a candidate.10 At least some of the organization’s spending may thus represent a shift from issue advertising, which is not disclosed to the FEC, to candidate advertising, which is disclosed, rather than new political spending spurred by Citizens United. However, even if the expenditures reported by trade associations are viewed as a result of the change in the law, the amounts spent advocating candidates, while meaningful, were relatively insignificant. In all, monies spent independently by individual companies and trade associations combined constituted less than five percent of the monies that came from unlimited sources in each of the past two elections and less than one percent of the total monies raised and spent in the entire election cycle.

Super PAC Contributions

Super PACs are responsible for most of the money raised from unlimited sources and most of the independent spending that can be attributed to Citizens United. These committees spent $345 million on independent expenditures in support of candidates in 2014 and three times as much, $1.1 billion, in 2016.11 The spending of these committees, therefore, dwarfed the sums disbursed on independent expenditures by all other entities that can be linked to Citizens United.

Where does this money come from? To answer this question, CED conducted an analysis of the contributions received by the top Super PACs, which were responsible for a large majority of total Super PAC receipts. For 2014, we examined the contributions received by the top 54 Super PACs ranked by total receipts, which were responsible for 87 percent of the money raised by the 1,360 Super PACs registered with the FEC. For 2016, we examined contributions received by the top 90 Super PACs, which were responsible for 94 percent of the money raised by 2,389 committees. Super PACs are required to disclose contributions of $200 or more, so these itemized contributions, which totaled more than $489 million in 2014 and more than $1.3 billion in 2016, were the basis for our analysis. These contributions constituted 70 percent of the money raised by Super PACs in 2014 and 81 percent of Super PAC receipts in 2016.

The findings of our analysis are presented in Tables 4 and 5, and depicted in Figures 1 and 2. As these tables note, a share of the money raised by Super PACs comes from other Super PACs, since some Super PACs use money they raise to make contributions to other Super PACs. In 2014, Super PAC to Super PAC contributions totaled $26 million, or 5 percent of total receipts. In 2016, this sum rose dramatically to $154 million, or 10 percent of total receipts. Much of this activity is due to the behavior of labor Super PACs, which receive money from unions and then work with other Super PACs to support their preferred candidates. For determining the total amount raised by Super PACs that is presented in our summary of federal campaign finance (see tables 1 and 2), these sums are deducted to avoid double counting.

Individual Donors

Individual donors are the primary source of Super PAC money and are responsible for the bulk of Super PAC receipts. In 2014, individuals gave $299 million to Super PACs, which represented 60 percent of their total receipts. In 2016, individuals gave more than three times as much, almost $1.1 billion, which made up 68 percent of Super PAC receipts. In addition, some individuals chose to make contributions from personal or family trust funds or revocable trusts, rather than personal bank accounts. In 2014, contributions from trust funds amounted to $13.6 million, including $7 million given to Freedom Partners Action Fund from the trusts of Charles and David Koch. In 2016, $6 million was contributed from trusts. In other words, individuals, including a relatively small number of individuals who make seven or eight figure contributions, have been responsible for the dramatic growth of Super PACs.

Business Contributions

Business corporations have not been a major source of Super PAC money. Business corporations were the source of about 5 percent of Super PAC receipts in 2014 and 6 percent in 2016, although the amount contributed in 2016, $95 million, represented a significant increase over the $25 million in total donations in 2014. The vast majority of business money comes from private companies or for-profit entities, including many small companies, law firms, medical practices, real estate brokerages and listing services, and limited liability corporations, many of which give modest amounts of $20,000 or less. Private businesses were the source of 80 percent of the money contributed by corporations in 2014 and 88 percent in 2016.

Accordingly, only a minor share of the money from business sources comes from publicly held companies. We adopted a broad definition of publicly held companies to include not only companies listed on public exchanges, but also a corporate entity owned or controlled by a publicly held company, any company or holding company with a publicly traded subsidiary, or any company or holding company with a majority interest in a publicly traded company. Even with this broad definition, we found that relatively few publicly held companies made donations to Super PACs. In 2014, 39 public companies made contributions to Super PACs, giving a total of $4.6 million. In 2016, 55 publicly traded companies made contributions to Super PACs, giving a total of $10.5 million. Donations from these companies thus constituted a small share of total business giving, totaling 20 percent of all business contributions in 2014 and 11 percent in 2016. In both elections, publicly held companies were the source of less than 1 percent of the total amount raised by Super PACs.

Moreover, most of the money donated by publicly held corporations came from only a few companies. In 2014, three companies were responsible for three-quarters of the $4.6 million total.12 In 2016, five companies were responsible for more than half of the $10.5 million total.13 At least to date, major corporations have not been active participants in Super PAC financing.

Trade associations are an even less important source of Super PAC money. Trade associations gave $11 million in 2014 and $12 million in 2016, which represented less than one percent of total Super PAC receipts. This funding was almost solely due to the National Association of Realtors, which contributed about $10 million in each of the past two elections, or more than 85 percent of the total for all trade associations.

Most of the money donated by business sources, including corporations and trade associations, went to a small number of Super PACs. More than half of the money contributed by business sources ($15.4 million) in 2014 went to five Super PACs: American Crossroads ($5.8 million) and Freedom Partners Action Fund ($4.0 million), which supported Republican candidates for Congress; Congressional Leadership Fund ($2.5 million), a committee associated with the Republican congressional leadership; and Senate Majority PAC ($1.6 million) and House Majority PAC ($1.5 million), which are committees associated with the Democratic Senate and House leadership.

In 2016, the increase in business donations to Super PACs was largely due to the amounts received by a few Super PACs formed to support specific presidential candidates. A major share of the money contributed by business sources went to only three Super PACs: Right to Rise USA ($26.5 million), which supported Jeb Bush; Conservative Solutions ($13.4 million), which supported Marco Rubio; and Priorities USA Action ($3 million), which supported Hillary Clinton. The only other Super PAC to raise a substantial amount from business was the Senate Leadership Fund ($12.9 million), a committee associated with the Republican Senate leadership. The Congressional Leadership Fund ($3.3 million) was another top recipient. About 60 percent of business money thus went to partyoriented committees formed to elect Republicans to Congress or committees formed to support candidates who were expected to be leading presidential contenders, none of whom won the race for the Oval Office.

Labor Contributions

Labor unions have been as active as the business community in making contributions to Super PACs. The major difference in behavior as compared to corporations is that several unions have established their own Super PACs, which are financed from labor union treasury accounts or other sources they control. Like corporate donations, the amounts unions have contributed make up a small share of total Super PAC receipts, although the amounts involved are substantial. In the past two elections combined, labor union donations have exceeded the total amount given by business corporations and trade groups by $32 million. In 2014, labor unions gave $81.6 million, which made up 17 percent of total Super PAC receipts. This sum was more than twice the amount that business sources contributed in 2014. In 2016, labor unions contributed $93 million, which was equivalent to the amount contributed by corporations, but slightly less than the $107 million given by corporations and trade associations combined.

In both elections, the leading union contributor was the National Education Association, which donated $22 million and $18.7 million, respectively, most of which went to its own Super PAC. Excluding the committees established by unions, the Super PACs that received the largest sums from labor sources in 2014 were the party-oriented committees focused on electing Democrats to Congress: Senate Majority PAC received $11.7 million, while House Majority PAC received more than $7.9 million. A quarter of the money contributed by unions went to these two committees. In 2016, Senate Majority PAC received $1.4 million and House Majority PAC, $1.8 million, which again placed them among the top three nonlabor committees to receive union funding. The top committee was Priorities USA Action, which supported Hillary Clinton and received a total of $5.2 million.

Group Contributions

Interest groups, including many that are organized as social welfare groups under the tax code, are also a source of Super PAC money. These groups, however, are not required to disclose the original sources of their funding, so we do not know the extent to which they are relying on financing from business sources, labor unions, individuals, or other groups. It is likely that some businesses support groups that make contributions to Super PACs. The same is true for labor unions or individual donors. This approach allows a company or other donor to avoid any reputational risks that may be associated with donations to independent organizations or, particularly in the case of retail businesses, any customer concerns that may result from political contributions. Publicly held companies may also give to nonprofit groups to avoid disclosure due to shareholder concerns. Given the controversies that have emerged over Internal Revenue Service investigations into the political activity of some nonprofit organizations, some companies may also be concerned about the risks associated with Internal Revenue Service audits or some other form of political payback. Similarly, individual donors may wish to make undisclosed contributions to avoid the publicity that may accompany disclosure, particularly given the media attention that large donors to Super PACs tend to attract.

Consequently, our analysis of Super PAC contributions was limited by the parameters of current disclosure rules. We were able to identify the nonprofit organizations that made contributions to Super PACs, and their donations made up less than 5 percent of Super PAC receipts, with total donations amounting to $15 million in 2014 and $70 million in 2016.

It is certainly the case that these groups receive donations from various types of donors and are not primarily financed from business sources. We base this conclusion on the character of the organizations involved. For example, in 2014, the top five groups that gave money to Super PACs were responsible for almost half ($7 million) of the total contributed by all groups. They were:

- Council for Job Growth, LLC ($2 million);

- AFT Solidarity 527, a nonfederal labor political committee sponsored by the American Federation of Teachers ($1.8 million);

- Susan B. Anthony List, a social welfare advocacy group that supports pro-life candidates ($1.776 million);

- Fair Share, Inc., a social welfare advocacy group that supports progressive principles ($800,000);

- Campion Advocacy Fund, a social welfare advocacy group focused on homelessness and wilderness protection ($700,000).

In 2016, the top five groups that gave money to Super PACs were responsible for 80 percent ($56 million) of all group donations to Super PACs. They were:

- One Nation, a conservative organization led by Senator Mitch McConnell’s former chief of staff ($20 million);

- Priorities USA, a progressive organization formed to support President Obama that supported Hillary Clinton in the presidential race ($14.5 million);

- AFT Solidarity 527, a nonfederal labor political committee sponsored by the American Federation of Teachers ($10.9 million);

- Environment America and its state-based affiliates, an environmental protection advocacy organization ($6.8 million);

- American Bridge 21st Century, a progressive organization that conducts research in support of Democratic candidates ($3.6 million).

Given the purposes and character of these organizations, we believe that it is highly unlikely that a major share of their financing came from business organizations. However, even if we assume that 75 percent of the money donated by groups to Super PACs came from business sources, which we consider a high estimate, the total share of Super PAC receipts from corporations, trade associations, professional organizations, and other for-profit entities, would still comprise less than 10 percent of the money raised by Super PACs in the past two elections.

The Limits of Transparency

We recognize that a complete analysis of the landscape of campaign financing is limited by the current state of disclosure rules. As we discussed in our report, Hidden Money: The Need for Transparency in Political Finance, present disclosure rules do not permit a full accounting of the money used in federal elections to advocate the election of candidates.14 In particular, we cannot determine the sources of funding for the independent expenditures that are made by nonprofit 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations, which are an important component of the unlimited spending that now takes place in federal elections. For the purposes of our analysis, we assume that all independent expenditures made by trade associations are from business sources, while all independent expenditures made by labor organizations are from monies that come from labor unions. But no simple assumption can be made about the sources of funds used by social welfare organizations.

How much of the spending done by nonprofit organizations represents new money spurred by Citizens United as opposed to a shift in the type of spending done by these organizations is impossible to determine. These organizations are allowed to spend unlimited sums of money on election-related activities that are not considered election spending under the law, including issue advertising, advertisements featuring federal candidates that are not aired close to an election, nonpartisan voter registration drives, or other activities that do not constitute express candidate advocacy. Some of the money they spend may represent a shift from issue advertising to candidate advertising. Even so, many of the nonprofit policy groups now active in elections were established since Citizens United and are playing an increasing role in the financing of campaigns. As indicated by our overview of federal campaign financing in Tables 1 and 2, these organizations financed $119 million of independent expenditures in 2014 and $147 million in 2016. Most of this money was spent by a small number of groups, with the top six spenders responsible for a major share of the money spent independently in each of the past two elections. These top spenders constituted a mixed group of organizations in each of the past two elections. According to the summaries of independent expenditures compiled by the FEC, six groups spent a total of $91 million in 2014: Crossroads Grassroots Policy Strategies, which is affiliated with American Crossroads, reported spending $42.1 million; National Rifle Association Institute for Legislative Action, $11.5 million; Patriot Majority USA, a progressive organization that supports Democratic candidates and receives union funding, $10.7 million; League of Conservation Voters, a membership-based environmental group, $9.5 million; American Action Network, which supported Republican candidates, $8.9 million; and Kentucky Opportunity Society, which supported the reelection of Senator Mitch McConnell, $8.2 million. In 2016, the top six groups spent $87 million: National Rifle Association Institute for Legislative Action, $33.3 million; 45 Committee, a conservative organization that opposed Hillary Clinton, $21.3 million; Americans for Prosperity, $14.3 million, and American Future Fund, $11.7 million, which supported Republican candidates; Majority Forward, a liberal group that supported Democratic candidates, $10.1 million; and League of Conservation Voters, $7 million.15

Given the diverse character of these groups, it is likely that they receive funding from diverse sources. Due to the lack of disclosure, meaningful assumptions about the relative role of different sources are impossible to make.

Conclusion

The campaign finance landscape is changing in the wake of Citizens United as new sources of funding and new types of organizations have become involved in federal elections due to the more permissive regulatory environment resulting from the Court’s decision. Yet, even with these changes, the vast majority of the money in federal elections still comes from the limited, disclosed contributions made by individual donors to candidates, parties, and PACs. In the past two elections, these limited sources were responsible for 82 percent and 76 percent, respectively, of the money reported as election spending. The remaining share came from unlimited sources that are for the most part related to the changes brought about by Citizens United, with the vast majority of this money attributable to Super PACs, which disclose their contributions and expenditures to the public.

The rise of Super PACs constitutes the major change that has occurred since Citizens United, and this development was a result of the appellate court decision in SpeechNow.org, rather than a direct ruling in Citizens United, although the court did rely on Citizens United in reaching its conclusion. Most of the money raised by Super PACs, 60 percent in 2014 and 68 percent in 2016, came from individual donors, not organizational sources. Consequently, when these unlimited individual contributions are added to the limited donations made by individuals, the vast majority of the money raised to finance election activity, 88 percent in 2014 and 90 percent in 2016, came from voluntary contributions made by individuals.

The end of the prohibition on the use of corporate and labor union treasury funds in federal elections has certainly influenced the contours of the campaign finance landscape. Corporations, labor unions, and other organizations have become more active participants in campaign finance and are spending substantial amounts, although this activity represents a minor share of the money flowing into federal elections. Corporate political behavior, however, has not changed dramatically since Citizens United. Our analysis indicates that business corporations and business organizations have not responded to the Citizens United ruling by devoting significant resources to election spending. The flood of corporate spending predicted at the time the decision was announced is not evident in the financing of the past two elections.

Business corporations have not been a significant source of independent spending. No major corporations have spent money independently in support of candidates and only a handful of companies or trade associations have chosen to do so. In fact, corporations have spent minuscule amounts and most of the spending is due to only one association, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. To put this spending in perspective, all independent expenditures by business corporations and business organizations represented less than 5 percent of the $788 million in total independent expenditures reported by the FEC in 2014 and about 2 percent of the $1.6 billion of independent expenditures in 2016. If the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is not included, business spending was less than one-half of one percent (0.5 percent) of the independent spending that occurred in each of the past two elections. Business corporations also have not been a significant source of Super PAC funding. Only a minor share of the monies raised by Super PACs has come from business sources, and the vast majority of business contributions come from private companies, including many small companies. Relatively few publicly held companies have made donations to Super PACs and these companies are responsible for less than one percent of Super PAC receipts, with most of this money coming from no more than five companies in each of the past two elections.

Similarly, labor unions and labor organizations have been active in Super PAC funding, but their contributions also constitute a minor share of Super PAC receipts. Based on our analysis of the donations received by the top Super PACs, the total sum contributed to Super PACs by labor unions and labor organizations has exceeded the total amount contributed by business sources by $32 million over the course of the past two elections. From what can be discerned from public reports, it is fair to say that the responses of the business community and labor community have been relatively equivalent in terms of their respective roles as sources of unlimited money in the election process: neither has pursued extensive independent spending and neither has proven to be a source of funding that is driving the growth of Super PAC fundraising, although both have contributed to the changes taking place in election finance in minor ways.

There has been a rising role and outpouring of money from interest groups, particularly nonprofit organizations that raise money outside the realm of public disclosure. The independent expenditures of these organizations represent 14 percent of the unlimited funding in 2014 and 8 percent in 2016. These groups have also been the source of a minor share of Super PAC money. The role of these organizations continues to be a cause for concern, since their transactions devoted to election spending are not subject to effective and full public disclosure. Further growth in this component of federal election finance in the years ahead will thus further impair the public’s ability to know who is behind election spending and thereby decrease the accountability in the campaign finance system.

About the Study

To determine the landscape of campaign spending and contributions in the wake of Citizens United, we examined all independent expenditures and electioneering communications made in the 2014 and 2016 election cycles.

We also examined the contributions reported by the top Super PACs in the 2014 and 2016 election cycle.

CED examined the contributions received by the top 53 Super PACs in the 2014 election, which raised a total of $598 million, or more than 80% of the total amount raised by all Super PACs. We also examined the top 90 committees in 2016, which raised $1.6 billion, or more than 90% of total raised by all Super PACs that year. In all, we cataloged almost $489 million of itemized Super PAC contributions in 2014 and $1.6 billion of itemized Super PAC contributions in 2016 by the type of donor to gain insights into the sources of Super PAC funding.

We separated the contributions from individuals from the contributions made by any organizational or non-individual donor. We cataloged more than 1,900 separate organizational contributions for 2014 and more than 3,200 separate organizational contributions in 2016. We then identified the organizational or non-individual donors by type of organization or source, based on background research conducted on each donor. We therefore focused on the type of organization, not the particular legal form of an entity. So, for example, a group organized as a nonprofit corporation or LLC was identified as a group, not a corporation. The categories were:

- Super PACs: Contributions made from one Super PAC to another. This category includes any “Carey Committees,” which are committees that have a Super PAC and a regular PAC account, if the contribution came from the unlimited Super PAC account.

- PACs: This category includes federally registered political action committees.

- Business Corporations: This category includes all business corporations or fee-for-service entities, including real estate listing services, law firms, medical partnerships or practices, limited liability corporations, insurance cooperatives, or public utilities.

- Trade Associations: This category includes trade associations or professional organizations, including real estate associations, hospital associations, medical associations, and river pilots associations.

- Unions: This category includes union treasury accounts or union entities that are not PACs or Super PACs, such as general treasury accounts, political education accounts, and advocacy accounts.

- Groups: This category includes nonprofit organizations and interest groups, such as environmental advocacy organizations, state education associations, nonfederal political committees and committees organized under section 527 of the tax code, 501(c)(4) social welfare groups, and comparable organizations.

- Trusts: This category includes trusts, typically established by an individual or family. Some individual donors make contributions from trust funds rather than some other personal banking account.

- Native American Organizations: This category includes accounts or entities established or controlled by Native American Tribes.

- Other: This category includes entities not covered by other categories, including candidate campaign committees, political party committees, and ballot or referendum committees.

Endnotes

- The totals for independent spending by Super PACs are based on the summaries of FEC data reported by the Center for Responsive Politics. These summaries can be found at https://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/fes_summ.php.

- These figures are based on our compilation and analysis of the disclosure reports filed by Super PACs with the FEC. See “About the Study” on page 22 for more detail.

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 50 (2010).

- SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, 599 F. 3d (D.C. Cir., March 26, 2010).

- President Barack Obama, Weekly Radio Address, January 23, 2010, http://thisweekwithbarackobama. blogspot.com/2010/01/president-obamas-weeklyaddress-january_23.html.

- See, among others, Jeffrey D. Clements, Corporations Are Not People (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2012).

- Our recent reports may be found at www.ced.org/projects/single/money-in-politics-project/all.

- In 2014, congressional candidates contributed or loaned $146.6 million to their own campaigns. In 2016, congressional candidates contributed or loaned $138.6 million to their own campaigns and presidential candidates contributed or loaned $79.6 million to their campaigns. See FEC, Congressional Candidate Table 1, www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2014/tables/congressional/ConCand1_2014_24m.pdf and www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2016/tables/congressional/ConCand1_2016_24m.pdf. For presidential candidates, see FEC, Presidential Table 1, http://www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2016/tables/presidential/PresCand1_2016_24m.pdf.

- Wendy L. Hansen, Michael S. Rocca, and Brittany Leigh Ortiz, “The Effects of Citizens United on Corporate Spending in the 2012 Presidential Election,” The Journal of Politics 77:2 (2015), 541. The four companies that made independent expenditures in 2012 were Melaleuca, Oasis Radio 1 Corp, Page Communications, and Wondros. See www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2012/tables/ie/IE2_2012_24m.pdf.

- Robert G. Boatright, “The Voice of American Business: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the 2010 Elections,” in Interest Groups Unleashed, edited by Paul S. Herrnson, Christopher J. Deering, and Clyde Wilcox (Congressional Quarterly Press, 2010), 36-38.

- The totals for independent spending by Super PACs are based on the summaries of FEC data reported by the Center for Responsive Politics. These summaries can be found at https://www.opensecrets.org/outsidespending/fes_summ.php.

- The three companies were: Contran, a private holding company that is included because it has a majority interest in Vahli, a publicly traded company ($1 million); Chevron ($1 million); and Alliance Resource Management and Alliance Resource Partners, which gave a combined $1.25 million.

- The five companies were: Chevron ($1.3 million); Nextera Energy ($1.275 million); Devon Energy ($1.250 million); Polar Tankers, a subsidiary of ConocoPhillips ($1 million); and GEO Group/GEO Corrections Holdings, a correctional facilities management company ($735,000).

- Committee for Economic Development, Hidden Money: The Need for Transparency in Political Finance (2011).

- These totals are drawn from compilation of independent expenditures by “persons other than political committees” in the FEC, “Table 1: Independent Expenditure Totals (Overall Summary Data).” The table for 2014 is found at www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2014/tables/ie/IE1_2014_24m.pdf. The table for 2016 is found at http://www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2016/ElectionCycle/24m_IE_EC.shtml.

The original report was published one CED's website.